Sliding mode control

In control theory, sliding mode control, or SMC, is a nonlinear control method that alters the dynamics of a nonlinear system by application of a discontinuous control signal that forces the system to "slide" along a cross-section of the system's normal behavior. The state-feedback control law is not a continuous function of time. Instead, it can switch from one continuous structure to another based on the current position in the state space. Hence, sliding mode control is a variable structure control method. The multiple control structures are designed so that trajectories always move toward an adjacent region with a different control structure, and so the ultimate trajectory will not exist entirely within one control structure. Instead, it will slide along the boundaries of the control structures. The motion of the system as it slides along these boundaries is called a sliding mode[1] and the geometrical locus consisting of the boundaries is called the sliding (hyper)surface. In the context of modern control theory, any variable structure system, like a system under SMC, may be viewed as a special case of a hybrid dynamical system as the system both flows through a continuous state space but also moves through different discrete control modes.

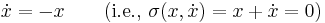

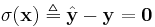

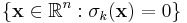

Figure 1 shows an example trajectory of a system under sliding mode control. The sliding surface is described by  , and the sliding mode along the surface commences after the finite time when system trajectories have reached the surface. In the theoretical description of sliding modes, the system stays confined to the sliding surface and need only be viewed as sliding along the surface. However, real implementations of sliding mode control approximate this theoretical behavior with a high-frequency and generally non-deterministic switching control signal that causes the system to "chatter" in a tight neighborhood of the sliding surface. This chattering behavior is evident in Figure 1, which chatters along the

, and the sliding mode along the surface commences after the finite time when system trajectories have reached the surface. In the theoretical description of sliding modes, the system stays confined to the sliding surface and need only be viewed as sliding along the surface. However, real implementations of sliding mode control approximate this theoretical behavior with a high-frequency and generally non-deterministic switching control signal that causes the system to "chatter" in a tight neighborhood of the sliding surface. This chattering behavior is evident in Figure 1, which chatters along the  surface as the system asymptotically approaches the origin, which is an asymptotically stable equilibrium of the system when confined to the sliding surface. In fact, although the system is nonlinear in general, the idealized (i.e., non-chattering) behavior of the system in Figure 1 when confined to the

surface as the system asymptotically approaches the origin, which is an asymptotically stable equilibrium of the system when confined to the sliding surface. In fact, although the system is nonlinear in general, the idealized (i.e., non-chattering) behavior of the system in Figure 1 when confined to the  surface is an LTI system with an exponentially stable origin.

surface is an LTI system with an exponentially stable origin.

Intuitively, sliding mode control uses practically infinite gain to force the trajectories of a dynamic system to slide along the restricted sliding mode subspace. Trajectories from this reduced-order sliding mode have desirable properties (e.g., the system naturally slides along it until it comes to rest at a desired equilibrium). The main strength of sliding mode control is its robustness. Because the control can be as simple as a switching between two states (e.g., "on"/"off" or "forward"/"reverse"), it need not be precise and will not be sensitive to parameter variations that enter into the control channel. Additionally, because the control law is not a continuous function, the sliding mode can be reached in finite time (i.e., better than asymptotic behavior). Under certain common conditions, optimality requires the use of bang–bang control; hence, sliding mode control describes the optimal controller for a broad set of dynamic systems.

One application of sliding mode controllers is the control of electric drives operated by switching power converters.[2]:"Introduction" Because of the discontinuous operating mode of those converters, a discontinuous sliding mode controller is a natural implementation choice over continuous controllers that may need to be applied by means of pulse-width modulation or a similar technique[nb 1] of applying a continuous signal to an output that can only take discrete states.

Sliding mode control must be applied with more care than other forms of nonlinear control that have more moderate control action. In particular, because actuators have delays and other imperfections, the hard sliding-mode-control action can lead to chatter, energy loss, plant damage, and excitation of unmodeled dynamics.[3]:554–556 Continuous control design methods are not as susceptible to these problems and can be made to mimic sliding-mode controllers.[3]:556–563

Contents |

Control scheme

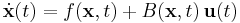

Consider a nonlinear dynamical system described by

|

|

|

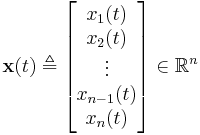

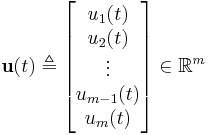

where

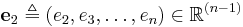

is an  -dimensional state vector and

-dimensional state vector and

is an  -dimensional input vector that will be used for state feedback. The functions

-dimensional input vector that will be used for state feedback. The functions  and

and  are assumed to be continuous and sufficiently smooth so that the Picard–Lindelöf theorem can be used to guarantee that solution

are assumed to be continuous and sufficiently smooth so that the Picard–Lindelöf theorem can be used to guarantee that solution  to Equation (1) exists and is unique.

to Equation (1) exists and is unique.

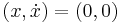

A common task is to design a state-feedback control law  (i.e., a mapping from current state

(i.e., a mapping from current state  at time

at time  to the input

to the input  ) to stabilize the dynamical system in Equation (1) around the origin

) to stabilize the dynamical system in Equation (1) around the origin ![\mathbf{x} = [0, 0, \ldots, 0]^{\text{T}}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5d1544c62294a862efb1f74594a98fac.png) . That is, under the control law, whenever the system is started away from the origin, it will return to it. For example, the component

. That is, under the control law, whenever the system is started away from the origin, it will return to it. For example, the component  of the state vector

of the state vector  may represent the difference some output is away from a known signal (e.g., a desirable sinusoidal signal); if the control

may represent the difference some output is away from a known signal (e.g., a desirable sinusoidal signal); if the control  can ensure that

can ensure that  quickly returns to

quickly returns to  , then the output will track the desired sinusoid. In sliding-mode control, the designer knows that the system behaves desirably (e.g., it has a stable equilibrium) provided that it is constrained to a subspace of its configuration space. Sliding mode control forces the system trajectories into this subspace and then holds them there so that they slide along it. This reduced-order subspace is referred to as a sliding (hyper)surface, and when closed-loop feedback forces trajectories to slide along it, it is referred to as a sliding mode of the closed-loop system. Trajectories along this subspace can be likened to trajectories along eigenvectors (i.e., modes) of LTI systems; however, the sliding mode is enforced by creasing the vector field with high-gain feedback. Like a marble rolling along a crack, trajectories are confined to the sliding mode.

, then the output will track the desired sinusoid. In sliding-mode control, the designer knows that the system behaves desirably (e.g., it has a stable equilibrium) provided that it is constrained to a subspace of its configuration space. Sliding mode control forces the system trajectories into this subspace and then holds them there so that they slide along it. This reduced-order subspace is referred to as a sliding (hyper)surface, and when closed-loop feedback forces trajectories to slide along it, it is referred to as a sliding mode of the closed-loop system. Trajectories along this subspace can be likened to trajectories along eigenvectors (i.e., modes) of LTI systems; however, the sliding mode is enforced by creasing the vector field with high-gain feedback. Like a marble rolling along a crack, trajectories are confined to the sliding mode.

The sliding-mode control scheme involves

- Selection of a hypersurface or a manifold (i.e., the sliding surface) such that the system trajectory exhibits desirable behavior when confined to this manifold.

- Finding feedback gains so that the system trajectory intersects and stays on the manifold.

Because sliding mode control laws are not continuous, it has the ability to drive trajectories to the sliding mode in finite time (i.e., stability of the sliding surface is better than asymptotic). However, once the trajectories reach the sliding surface, the system takes on the character of the sliding mode (e.g., the origin  may only have asymptotic stability on this surface).

may only have asymptotic stability on this surface).

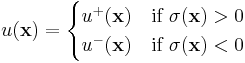

The sliding-mode designer picks a switching function  that represents a kind of "distance" that the states

that represents a kind of "distance" that the states  are away from a sliding surface.

are away from a sliding surface.

- A state

that is outside of this sliding surface has

that is outside of this sliding surface has  .

. - A state that is on this sliding surface has

.

.

The sliding-mode-control law switches from one state to another based on the sign of this distance. So the sliding-mode control acts like a stiff pressure always pushing in the direction of the sliding mode where  . Desirable

. Desirable  trajectories will approach the sliding surface, and because the control law is not continuous (i.e., it switches from one state to another as trajectories move across this surface), the surface is reached in finite time. Once a trajectory reaches the surface, it will slide along it and may, for example, move toward the

trajectories will approach the sliding surface, and because the control law is not continuous (i.e., it switches from one state to another as trajectories move across this surface), the surface is reached in finite time. Once a trajectory reaches the surface, it will slide along it and may, for example, move toward the  origin. So the switching function is like a topographic map with a contour of constant height along which trajectories are forced to move.

origin. So the switching function is like a topographic map with a contour of constant height along which trajectories are forced to move.

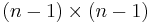

The sliding (hyper)surface is of dimension  where

where  is the number of states in

is the number of states in  and

and  is the number of input signals (i.e., control signals) in

is the number of input signals (i.e., control signals) in  . For each control index

. For each control index  , there is an

, there is an  sliding surface given by

sliding surface given by

|

|

|

The vital part of VSC design is to choose a control law so that the sliding mode (i.e., this surface given by  ) exists and is reachable along system trajectories. The principle of sliding mode control is to forcibly constrain the system, by suitable control strategy, to stay on the sliding surface on which the system will exhibit desirable features. When the system is constrained by the sliding control to stay on the sliding surface, the system dynamics are governed by reduced-order system obtained from Equation (2).

) exists and is reachable along system trajectories. The principle of sliding mode control is to forcibly constrain the system, by suitable control strategy, to stay on the sliding surface on which the system will exhibit desirable features. When the system is constrained by the sliding control to stay on the sliding surface, the system dynamics are governed by reduced-order system obtained from Equation (2).

To force the system states  to satisfy

to satisfy  , one must:

, one must:

- Ensure that the system is capable of reaching

from any initial condition

from any initial condition - Having reached

, the control action is capable of maintaining the system at

, the control action is capable of maintaining the system at

Existence of closed-loop solutions

Note that because the control law is not continuous, it is certainly not locally Lipschitz continuous, and so existence and uniqueness of solutions to the closed-loop system is not guaranteed by the Picard–Lindelöf theorem. Thus the solutions are to be understood in the Filippov sense.[1][4] Roughly speaking, the resulting closed-loop system moving along  is approximated by the smooth dynamics

is approximated by the smooth dynamics  ; however, this smooth behavior may not be truly realizable. Similarly, high-speed pulse-width modulation or delta-sigma modulation produces outputs that only assume two states, but the effective output swings through a continuous range of motion. These complications can be avoided by using a different nonlinear control design method that produces a continuous controller. In some cases, sliding-mode control designs can be approximated by other continuous control designs.[3]

; however, this smooth behavior may not be truly realizable. Similarly, high-speed pulse-width modulation or delta-sigma modulation produces outputs that only assume two states, but the effective output swings through a continuous range of motion. These complications can be avoided by using a different nonlinear control design method that produces a continuous controller. In some cases, sliding-mode control designs can be approximated by other continuous control designs.[3]

Theoretical foundation

The following theorems form the foundation of variable structure control.

Theorem 1: Existence of Sliding Mode

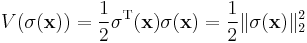

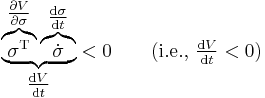

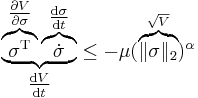

Consider a Lyapunov function candidate

|

|

|

where  is the Euclidean norm (i.e.,

is the Euclidean norm (i.e.,  is the distance away from the sliding manifold where

is the distance away from the sliding manifold where  ). For the system given by Equation (1) and the sliding surface given by Equation (2), a sufficient condition for the existence of a sliding mode is that

). For the system given by Equation (1) and the sliding surface given by Equation (2), a sufficient condition for the existence of a sliding mode is that

in a neighborhood of the surface given by  .

.

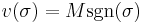

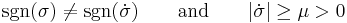

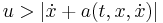

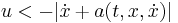

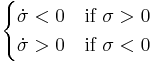

Roughly speaking (i.e., for the scalar control case when  ), to achieve

), to achieve  , the feedback control law

, the feedback control law  is picked so that

is picked so that  and

and  have opposite signs. That is,

have opposite signs. That is,

makes

makes  negative when

negative when  is positive.

is positive. makes

makes  positive when

positive when  is negative.

is negative.

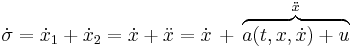

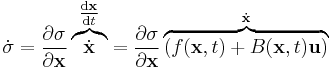

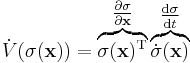

Note that

and so the feedback control law  has a direct impact on

has a direct impact on  .

.

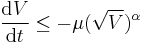

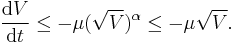

Reachability: Attaining sliding manifold in finite time

To ensure that the sliding mode  is attained in finite time,

is attained in finite time,  must be more strongly bounded away from zero. That is, if it vanishes too quickly, the attraction to the sliding mode will only be asymptotic. To ensure that the sliding mode is entered in finite time,[5]

must be more strongly bounded away from zero. That is, if it vanishes too quickly, the attraction to the sliding mode will only be asymptotic. To ensure that the sliding mode is entered in finite time,[5]

where  and

and  are constants.

are constants.

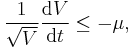

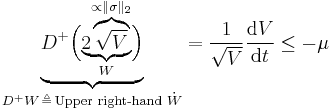

- Explanation by comparison lemma

This condition ensures that for the neighborhood of the sliding mode ![V \in [0,1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c6a3204a8d439860a8bfc3a550874714.png) ,

,

So, for ![V \in (0,1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6892fe5bf6514b7ece5aa48323b670c6.png) ,

,

which, by the chain rule (i.e.,  with

with  ), means

), means

where  is the upper right-hand derivative of

is the upper right-hand derivative of  and the symbol

and the symbol  denotes proportionality. So, by comparison to the curve

denotes proportionality. So, by comparison to the curve  which is represented by differential equation

which is represented by differential equation  with initial condition

with initial condition  , it must be the case that

, it must be the case that  for all

for all  . Moreover, because

. Moreover, because  ,

,  must reach

must reach  in finite time, which means that

in finite time, which means that  must reach

must reach  (i.e., the system enters the sliding mode) in finite time.[3] Because

(i.e., the system enters the sliding mode) in finite time.[3] Because  is proportional to the Euclidean norm

is proportional to the Euclidean norm  of the switching function

of the switching function  , this result implies that the rate of approach to the sliding mode must be firmly bounded away from zero.

, this result implies that the rate of approach to the sliding mode must be firmly bounded away from zero.

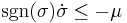

- Consequences for sliding mode control

In the context of sliding mode control, this condition means that

where  is the Euclidean norm. For the case when switching function

is the Euclidean norm. For the case when switching function  is scalar valued, the sufficient condition becomes

is scalar valued, the sufficient condition becomes

.

.

Taking  , the scalar sufficient condition becomes

, the scalar sufficient condition becomes

which is equivalent to the condition that

.

.

That is, the system should always be moving toward the switching surface  , and its speed

, and its speed  toward the switching surface should have a non-zero lower bound. So, even though

toward the switching surface should have a non-zero lower bound. So, even though  may become vanishingly small as

may become vanishingly small as  approaches the

approaches the  surface,

surface,  must always be bounded firmly away from zero. To ensure this condition, sliding mode controllers are discontinuous across the

must always be bounded firmly away from zero. To ensure this condition, sliding mode controllers are discontinuous across the  manifold; they switch from one non-zero value to another as trajectories cross the manifold.

manifold; they switch from one non-zero value to another as trajectories cross the manifold.

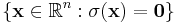

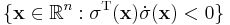

Theorem 2: Region of Attraction

For the system given by Equation (1) and sliding surface given by Equation (2), the subspace for which the  surface is reachable is given by

surface is reachable is given by

That is, when initial conditions come entirely from this space, the Lyapunov function candidate  is a Lyapunov function and

is a Lyapunov function and  trajectories are sure to move toward the sliding mode surface where

trajectories are sure to move toward the sliding mode surface where  . Moreover, if the reachability conditions from Theorem 1 are satisfied, the sliding mode will enter the region where

. Moreover, if the reachability conditions from Theorem 1 are satisfied, the sliding mode will enter the region where  is more strongly bounded away from zero in finite time. Hence, the sliding mode

is more strongly bounded away from zero in finite time. Hence, the sliding mode  will be attained in finite time.

will be attained in finite time.

Theorem 3: Sliding Motion

Let

be nonsingular. That is, the system has a kind of controllability that ensures that there is always a control that can move a trajectory to move closer to the sliding mode. Then, once the sliding mode where  is achieved, the system will stay on that sliding mode. Along sliding mode trajectories,

is achieved, the system will stay on that sliding mode. Along sliding mode trajectories,  is constant, and so sliding mode trajectories are described by the differential equation

is constant, and so sliding mode trajectories are described by the differential equation

.

.

If an  -equilibrium is stable with respect to this differential equation, then the system will slide along the sliding mode surface toward the equilibrium.

-equilibrium is stable with respect to this differential equation, then the system will slide along the sliding mode surface toward the equilibrium.

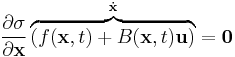

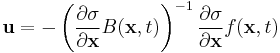

The equivalent control law on the sliding mode can be found by solving

for the equivalent control law  . That is,

. That is,

and so the equivalent control

That is, even though the actual control  is not continuous, the rapid switching across the sliding mode where

is not continuous, the rapid switching across the sliding mode where  forces the system to act as if it were driven by this continuous control.

forces the system to act as if it were driven by this continuous control.

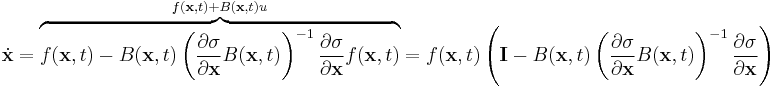

Likewise, the system trajectories on the sliding mode behave as if

The resulting system matches the sliding mode differential equation

and so as long as the sliding mode surface where  is stable (in the sense of Lyapunov), the system can be assumed to follow the simpler

is stable (in the sense of Lyapunov), the system can be assumed to follow the simpler  condition after some initial transient during the period while the system finds the sliding mode. The same motion is approximately maintained provided the equality

condition after some initial transient during the period while the system finds the sliding mode. The same motion is approximately maintained provided the equality  only approximately holds.

only approximately holds.

It follows from these theorems that the sliding motion is invariant (i.e., insensitive) to sufficiently small disturbances entering the system through the control channel. That is, as long as the control is large enough to ensure that  and

and  is uniformly bounded away from zero, the sliding mode will be maintained as if there was no disturbance. The invariance property of sliding mode control to certain disturbances and model uncertainties is its most attractive feature; it is strongly robust.

is uniformly bounded away from zero, the sliding mode will be maintained as if there was no disturbance. The invariance property of sliding mode control to certain disturbances and model uncertainties is its most attractive feature; it is strongly robust.

As discussed in an example below, a sliding mode control law can keep the constraint

in order to asymptotically stabilize any system of the form

when  has a finite upper bound. In this case, the sliding mode is where

has a finite upper bound. In this case, the sliding mode is where

(i.e., where  ). That is, when the system is constrained this way, it behaves like a simple stable linear system, and so it has a globally exponentially stable equilibrium at the

). That is, when the system is constrained this way, it behaves like a simple stable linear system, and so it has a globally exponentially stable equilibrium at the  origin.

origin.

Control design examples

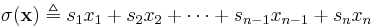

- Consider a plant described by Equation (1) with single input

(i.e.,

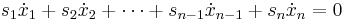

(i.e.,  ). The switching function is picked to be the linear combination

). The switching function is picked to be the linear combination

|

|

|

- where the weight

for all

for all  . The sliding surface is the simplex where

. The sliding surface is the simplex where  . When trajectories are forced to slide along this surface,

. When trajectories are forced to slide along this surface,

- and so

- which is a reduced-order system (i.e., the new system is of order

because the system is constrained to this

because the system is constrained to this  -dimensional sliding mode simplex). This surface may have favorable properties (e.g., when the plant dynamics are forced to slide along this surface, they move toward the origin

-dimensional sliding mode simplex). This surface may have favorable properties (e.g., when the plant dynamics are forced to slide along this surface, they move toward the origin  ). Taking the derivative of the Lyapunov function in Equation (3), we have

). Taking the derivative of the Lyapunov function in Equation (3), we have

- To ensure

is a negative-definite function (i.e.,

is a negative-definite function (i.e.,  for Lyapunov stability of the surface

for Lyapunov stability of the surface  ), the feedback control law

), the feedback control law  must be chosen so that

must be chosen so that

- Hence, the product

because it is the product of a negative and a positive number. Note that

because it is the product of a negative and a positive number. Note that

|

|

|

- The control law

is chosen so that

is chosen so that

- where

is some control (e.g., possibly extreme, like "on" or "forward") that ensures Equation (5) (i.e.,

is some control (e.g., possibly extreme, like "on" or "forward") that ensures Equation (5) (i.e.,  ) is negative at

) is negative at

is some control (e.g., possibly extreme, like "off" or "reverse") that ensures Equation (5) (i.e.,

is some control (e.g., possibly extreme, like "off" or "reverse") that ensures Equation (5) (i.e.,  ) is positive at

) is positive at

- The resulting trajectory should move toward the sliding surface where

. Because real systems have delay, sliding mode trajectories often chatter back and forth along this sliding surface (i.e., the true trajectory may not smoothly follow

. Because real systems have delay, sliding mode trajectories often chatter back and forth along this sliding surface (i.e., the true trajectory may not smoothly follow  , but it will always return to the sliding mode after leaving it).

, but it will always return to the sliding mode after leaving it).

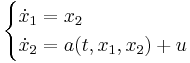

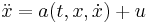

- Consider the dynamic system

-

- which can be expressed in a 2-dimensional state space (with

and

and  ) as

) as

- Also assume that

(i.e.,

(i.e.,  has a finite upper bound

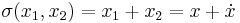

has a finite upper bound  that is known). For this system, choose the switching function

that is known). For this system, choose the switching function

- By the previous example, we must choose the feedback control law

so that

so that  . Here,

. Here,

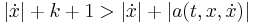

- When

(i.e., when

(i.e., when  ), to make

), to make  , the control law should be picked so that

, the control law should be picked so that

- When

(i.e., when

(i.e., when  ), to make

), to make  , the control law should be picked so that

, the control law should be picked so that

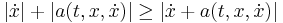

- However, by the triangle inequality,

- and by the assumption about

,

,

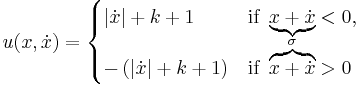

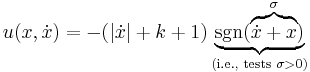

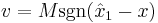

- So the system can be feedback stabilized (to return to the sliding mode) by means of the control law

- which can be expressed in closed form as

- Assuming that the system trajectories are forced to move so that

, then

, then

- So once the system reaches the sliding mode, the system's 2-dimensional dynamics behave like this 1-dimensional system, which has a globally exponentially stable equilibrium at

.

.

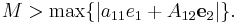

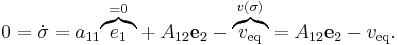

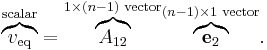

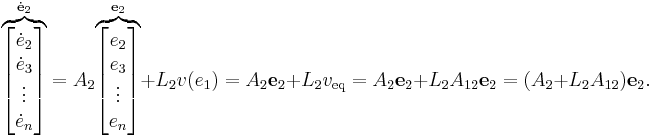

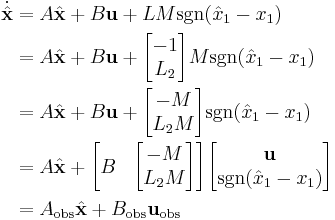

Sliding mode observer

Sliding mode control can be used in the design of state observers. These non-linear high-gain observers have the ability to bring coordinates of the estimator error dynamics to zero in finite time. Additionally, switched-mode observers have attractive measurement noise resilience that is similar to a Kalman filter.[6][7] For simplicity, the example here uses a traditional sliding mode modification of a Luenberger observer for an LTI system. In these sliding mode observers, the order of the observer dynamics are reduced by one when the system enters the sliding mode. In this particular example, the estimator error for a single estimated state is brought to zero in finite time, and after that time the other estimator errors decay exponentially to zero. However, as first described by Drakunov,[8] a sliding mode observer for non-linear systems can be built that brings the estimation error for all estimated states to zero in a finite (and arbitrarily small) time.

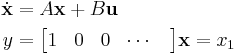

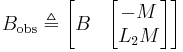

Here, consider the LTI system

where state vector  ,

,  is a vector of inputs, and output

is a vector of inputs, and output  is a scalar equal to the first state of the

is a scalar equal to the first state of the  state vector. Let

state vector. Let

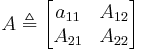

where

is a scalar representing the influence of the first state

is a scalar representing the influence of the first state  on itself,

on itself, is a column vector representing the influence of the other states on the first state,

is a column vector representing the influence of the other states on the first state, is a matrix representing the influence of the other states on themselves, and

is a matrix representing the influence of the other states on themselves, and is a row vector corresponding to the influence of the first state on the other states.

is a row vector corresponding to the influence of the first state on the other states.

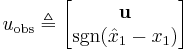

The goal is to design a high-gain state observer that estimates the state vector  using only information from the measurement

using only information from the measurement  . Hence, let the vector

. Hence, let the vector  be the estimates of the

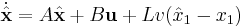

be the estimates of the  states. The observer takes the form

states. The observer takes the form

where  is a nonlinear function of the error between estimated state

is a nonlinear function of the error between estimated state  and the output

and the output  , and

, and  is an observer gain vector that serves a similar purpose as in the typical linear Luenberger observer. Likewise, let

is an observer gain vector that serves a similar purpose as in the typical linear Luenberger observer. Likewise, let

where  is a column vector. Additionally, let

is a column vector. Additionally, let  be the state estimator error. That is,

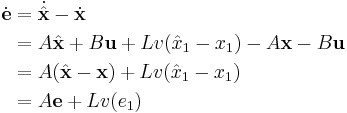

be the state estimator error. That is,  . The error dynamics are then

. The error dynamics are then

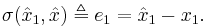

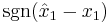

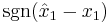

where  is the estimator error for the first state estimate. The nonlinear control law

is the estimator error for the first state estimate. The nonlinear control law  can be designed to enforce the sliding manifold

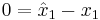

can be designed to enforce the sliding manifold

so that estimate  tracks the real state

tracks the real state  after some finite time (i.e.,

after some finite time (i.e.,  ). Hence, the sliding mode control switching function

). Hence, the sliding mode control switching function

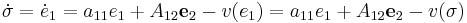

To attain the sliding manifold,  and

and  must always have opposite signs (i.e.,

must always have opposite signs (i.e.,  for essentially all

for essentially all  ). However,

). However,

where  is the collection of the estimator errors for all of the unmeasured states. To ensure that

is the collection of the estimator errors for all of the unmeasured states. To ensure that  , let

, let

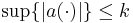

where

That is, positive constant  must be greater that a scaled version of the maximum possible estimator errors for the system (i.e., the initial errors, which are assumed to be bounded so that

must be greater that a scaled version of the maximum possible estimator errors for the system (i.e., the initial errors, which are assumed to be bounded so that  can be picked large enough; al). If

can be picked large enough; al). If  is sufficiently large, it can be assumed that the system achieves

is sufficiently large, it can be assumed that the system achieves  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  ). Because

). Because  is constant (i.e., 0) along this manifold,

is constant (i.e., 0) along this manifold,  as well. Hence, the discontinuous control

as well. Hence, the discontinuous control  may be replaced with the equivalent continuous control

may be replaced with the equivalent continuous control  where

where

So

This equivalent control  represents the contribution from the other

represents the contribution from the other  states to the trajectory of the output state

states to the trajectory of the output state  . In particular, the row

. In particular, the row  acts like an output vector for the error subsystem

acts like an output vector for the error subsystem

So, to ensure the estimator error  for the unmeasured states converges to zero, the

for the unmeasured states converges to zero, the  vector

vector  must be chosen so that the

must be chosen so that the  matrix

matrix  is Hurwitz (i.e., the real part of each of its eigenvalues must be negative). Hence, provided that it is observable, this

is Hurwitz (i.e., the real part of each of its eigenvalues must be negative). Hence, provided that it is observable, this  system can be stabilized in exactly the same way as a typical linear state observer when

system can be stabilized in exactly the same way as a typical linear state observer when  is viewed as the output matrix (i.e., "

is viewed as the output matrix (i.e., " "). That is, the

"). That is, the  equivalent control provides measurement information about the unmeasured states that can continually move their estimates asymptotically closer to them. Meanwhile, the discontinuous control

equivalent control provides measurement information about the unmeasured states that can continually move their estimates asymptotically closer to them. Meanwhile, the discontinuous control  forces the estimate of the measured state to have zero error in finite time. Additionally, white zero-mean symmetric measurement noise (e.g., Gaussian noise) only affects the switching frequency of the control

forces the estimate of the measured state to have zero error in finite time. Additionally, white zero-mean symmetric measurement noise (e.g., Gaussian noise) only affects the switching frequency of the control  , and hence the noise will have little effect on the equivalent sliding mode control

, and hence the noise will have little effect on the equivalent sliding mode control  . Hence, the sliding mode observer has Kalman filter–like features.[7]

. Hence, the sliding mode observer has Kalman filter–like features.[7]

The final version of the observer is thus

where

,

, , and

, and .

.

That is, by augmenting the control vector  with the switching function

with the switching function  , the sliding mode observer can be implemented as an LTI system. That is, the discontinuous signal

, the sliding mode observer can be implemented as an LTI system. That is, the discontinuous signal  is viewed as a control input to the 2-input LTI system.

is viewed as a control input to the 2-input LTI system.

For simplicity, this example assumes that the sliding mode observer has access to a measurement of a single state (i.e., output  ). However, a similar procedure can be used to design a sliding mode observer for a vector of weighted combinations of states (i.e., when output

). However, a similar procedure can be used to design a sliding mode observer for a vector of weighted combinations of states (i.e., when output  uses a generic matrix

uses a generic matrix  ). In each case, the sliding mode will be the manifold where the estimated output

). In each case, the sliding mode will be the manifold where the estimated output  follows the measured output

follows the measured output  with zero error (i.e., the manifold where

with zero error (i.e., the manifold where  ).

).

See also

- Variable structure control

- Variable structure system

- Hybrid system

- Nonlinear control

- Robust control

- Optimal control

- Bang–bang control – Sliding mode control is often implemented as a bang–bang control. In some cases, such control is necessary for optimality.

- H-bridge – A topology that combines four switches forming the four legs of an "H". Can be used to drive a motor (or other electrical device) forward or backward when only a single supply is available. Often used in actuator in sliding-mode controlled systems.

- Switching amplifier – Uses switching-mode control to drive continuous outputs

- Delta-sigma modulation – Another (feedback) method of encoding a continuous range of values in a signal that rapidly switches between two states (i.e., a kind of specialized sliding-mode control)

- Pulse density modulation – A generalized form of delta-sigma modulation.

- Pulse-width modulation – Another modulation scheme that produces continuous motion through discontinuous switching.

Notes

- ^ Other pulse-type modulation techniques include delta-sigma modulation.

References

- ^ a b Zinober, A.S.I., ed (1990). Deterministic control of uncertain systems. London: Peter Peregrinus Press. ISBN 978-0863411700.

- ^ Utkin, Vadim I. (1993). "Sliding Mode Control Design Principles and Applications to Electric Drives". IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics (IEEE) 40 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1109/41.184818.

- ^ a b c d Khalil, H.K. (2002). Nonlinear Systems (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-067389-7. http://www.egr.msu.edu/~khalil/NonlinearSystems/.

- ^ Filippov, A.F. (1988). Differential Equations with Discontinuous Right-hand Sides. Kluwer. ISBN 978-9027726995.

- ^ Perruquetti, W.; Barbot, J.P. (2002). Sliding Mode Control in Engineering. Marcel Dekker Hardcover. ISBN 0824706714.

- ^ Utkin, Vadim; Guldner, Jürgen; Shi, Jingxin (1999). Sliding Mode Control in Electromechanical Systems. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis, Inc.. ISBN 0-7484-0116-4.

- ^ a b Drakunov, S.V. (1983). "An adaptive quasioptimal filter with discontinuous parameters". Automation and Remote Control 44 (9): 1167–1175.

- ^ Drakunov, S.V. (1992). Sliding-Mode Observers Based on Equivalent Control Method. 2368–2370. ISBN 0-7803-0872-7. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=371368&isnumber=8509.

Further reading

- Acary, V.; Brogliato, B. (2008). Numerical Methods for Nonsmooth Dynamical Systems. Applications in Mechanics and Electronics. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, LNACM 35. ISBN 978-3-540-75391-9.

- Edwards, Cristopher; Fossas Colet, Enric; Fridman, Leonid, eds (2006). Advances in Variable Structure and Sliding Mode Control. Lecture Notes in Control and Information Sciences. vol 334. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-32800-1.

- Edwards, C.; Spurgeon, S. (1998). Sliding Mode Control: Theory and Applications. London: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0-7484-0601-8.

- Utkin, V.I. (1992). Sliding Modes in Control and Optimization. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0387535166.

- Zinober, Alan S.I., ed (1994). Variable Structure and Lyapunov Control. London: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/BFb0033675. ISBN 978-3-540-19869-7.

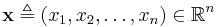

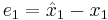

![\dot{\sigma}(\mathbf{x})

= \overbrace{\frac{\partial{\sigma(\mathbf{x})}}{\partial{\mathbf{x}}} \dot{\mathbf{x}}}^{\dot{\sigma}(\mathbf{x})}

= \frac{\partial{\sigma(\mathbf{x})}}{\partial{\mathbf{x}}}

\overbrace{\left( f(\mathbf{x},t) %2B B(\mathbf{x},t) u \right)}^{\dot{\mathbf{x}}}

= \overbrace{[s_1, s_2, \ldots, s_n]}^{\frac{\partial{\sigma(\mathbf{x})}}{\partial{\mathbf{x}}}}

\underbrace{\overbrace{\left( f(\mathbf{x},t) %2B B(\mathbf{x},t) u \right)}^{\dot{\mathbf{x}}}}_{\text{( i.e., an } n \times 1 \text{ vector )}}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0f262c8d3d49cdf4cc73dca9c03cf5bb.png)